Museum Moment: Irwin's Memorable 1990 Victory

By David Shefter, USGA

The beauty of the U.S. Open is its democratic format. Anyone eligible to participate can attempt to qualify, whether it’s the local club professional, an elite amateur or one of the world’s best golfers.

|

You had 45-year-old Hale Irwin, the grizzled veteran and winner of two previous U.S. Opens (1974 and 1979), who was only in the field thanks to a special exemption from the USGA. And you had the ultimate underdog in 34-year-old vagabond tour pro Mike Donald, whose only PGA Tour victory had come a year earlier in Williamsburg, Va.

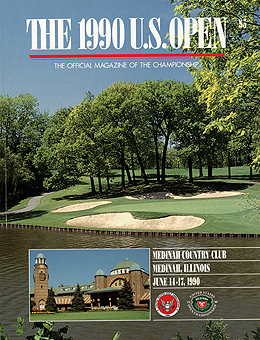

Such is the unpredictability of sports. But that June weekend at Medinah Country Club in suburban Chicago, where Curtis Strange unsuccessfully attempted to become the second player in history to win three consecutive U.S. Open titles, these two combatants provided the kind of major-championship theater people love.

Irwin came into that Open on a five-year winless drought. Five years away from being eligible for the 50-and-over Senior Tour, some thought the former University of Colorado defensive back’s best days were well behind him.

Donald, meanwhile, was just another anonymous member of the 156-player field who never had sniffed being in contention at a major.

Come Sunday’s final round, however, this obscure player found himself in the final pairing with another unheralded golfer, Billy Ray Brown. A third-round 72 (even par) had left Donald with a share of the 54-hole lead at seven-under-par 209 (with Brown). But it was a tight leader board. Forty-seven players were within seven strokes of the lead and 27 were within four shots. That group included Irwin, who had carded a disappointing 2-over 74 in Saturday’s third round.

Starting nearly two hours before the final group, Irwin’s main focus that Sunday was a top-15 finish to ensure him a spot in the 1991 Open field. That was his thought process when he glanced at the board near the 11th tee.

“My goal was to play the last eight holes in one under par,” said Irwin.

Whether it was experience or a rush of rekindled spirit, Irwin began playing like a two-time Open champion. He knocked a 6-iron approach to 6 feet for a birdie at No. 11. He stuck a long iron close at No. 12 (462-yard, par 4) for another birdie. Birdies at 13 (par 3) and 14 (par 5) put Irwin at seven under for the championship. Suddenly his thoughts went from being invited back to having his name engraved on the trophy.

Pars at 15, 16 and 17 set up one of the most dramatic moments in Open history. Facing a 45-foot cross-country birdie attempt, Irwin measured the line and speed to perfection to create bedlam at the 18th green. Once the putt fell, Irwin went bonkers, running around the green and high-fiving fans as if he had just returned an interception to beat Nebraska for the Big Eight Conference title.

“It may have been the most exciting moment in my entire professional career,” said Irwin. “It was just a matter of thanking [the fans] for being there and sharing this moment with me. It was pretty extraordinary.

“You look at any 45-foot putt [and] what are the odds? Not very good. This given putt at this given moment for this particular championship … it’s pretty special. It does lend itself to that quality of, ‘Are you kidding me?’ ”

That birdie gave Irwin a 5-under 67 and put him at 8-under 280. At the time, he thought that it would be good enough to tie, but not win the title outright.

That premonition proved to be correct. Several golfers were still on the course with a chance to win, mainly Donald and Brown, along with that year’s Masters champion, Nick Faldo.

Faldo sealed his fate with a three-putt bogey at 16 and a missed 12-foot birdie putt at 18. Brown did birdie the par-3 17th, but failed to birdie 18 to get into the playoff.

That left Donald, who was showing signs of nerves, but managing to escape with dramatic pars at 12 (35 feet) and 14 (15 feet). He missed a 12-footer for par at 16, which dropped him into a tie with Irwin. Steady pars at 17 and 18 put Donald in one of the unlikeliest of scenarios – a playoff against the veteran Irwin.

This was Jack Fleck versus Ben Hogan, or Francis Ouimet against Ted Ray and Harry Vardon.

Except the underdog didn’t win this showdown.

Despite less-than-stellar play, Irwin managed to rally for a 19-hole victory.

“That [Sunday] night was very difficult,” said Irwin of trying to regroup for the 18-hole Monday playoff. “You have to gather it up all over again. That’s hard to do.

“I was really flat and making errors.”

Donald appeared headed to victory with three holes to play. Irwin trailed by two shots and faced a tricky 199-yard approach to the par-4 16th green.

“I had to play a draw,” said Irwin. “If I pull it one yard [left], I am going to hit a tree.”

Irwin’s shot stopped 6 feet from the flagstick to set up a birdie. Both players made par at 17, meaning Irwin still had to make up a shot to force the first sudden-death situation in U.S. Open history. Back in 1946 at Canterbury C.C. when Lloyd Mangrum and Byron Nelson were deadlocked after the first 18 holes, they had to play another 18. That rule on 18-hole playoffs had been mercifully stricken by the USGA.

Donald surprised Irwin by hitting driver at the 440-yard finishing hole. Experience would have told Irwin to play an iron or fairway metal, but Donald, who had not hit many drivers all day, did so here and found trouble. When he failed to get up and down for par from a greenside bunker, the two were deadlocked after carding 2-over 74s.

Seizing the moment, Irwin executed a perfect sand-wedge approach at the 385-yard first hole to 10 feet. After Donald missed from 30 feet, Irwin clinched his third Open title by holing his birdie putt.

“Quite a glorious ending to an otherwise drab day,” said Irwin. “But the last hour of golf, I played pretty spectacular.

“I am proud of those [three] championships. The first one stamped my arrival. The second was kind of a certification that I am still here.”

And the third showed that a wily veteran could still find that magic.

As for Donald, he never got in contention again. This was his 15 minutes of fame, but he did get noticed a few more times during that Open week.

“I could see it at the airport,” Donald told the Orlando Sentinel just prior to the Westchester Open the following week. “People recognized me, and they came up and shook my hand and told me I played good. They were all excited about seeing me. This isn’t something that happens to me a lot.”

David Shefter is a USGA communications staff writer. E-mail him with questions or comments at dshefter@usga.org.