Watson Executed When It Mattered Most At 1982 U.S. Open

'That shot at 17 meant more to me than any golf shot I ever made,' he said

By Dave Shedloski

As spring turned to summer in 1982, Tom Watson, the PGA Tour’s Player of the Year in four of the past five seasons, found himself uncharacteristically struggling with his golf game. In fact, he was playing some of his worst golf in memory, and the timing couldn’t have been worse, with the 82nd U.S. Open fast approaching. Oddly, that turned out to be the best thing that could have happened as he arrived at Pebble Beach Golf Links for the second National Open at the historic seaside course.

Related Links Video: Watson Silences Golden Bear In 1982 Video: Nicklaus Reflects On 1972 Open Golf Journal Archives: Watson, Pebble Beach, And A Rivalry Revisited |

Watson’s two-stroke victory over four-time champion Jack Nicklaus is remembered most (and almost exclusively) for one signature moment: an impossibly delicate downhill chip shot on the par-3 17th hole that Watson holed for a birdie to help him secure his only U.S. Open Championship after years of frustrating near misses.

Believe what you want about fortune and fate, but the downhill 16-foot flop-gouge-chip that Watson was required to execute from a tangled web of rough might have been a championship killer for almost any other competitor – and Nicklaus, sitting in the scoring trailer watching on TV, was certain it was thus for his familiar foe. But there was no one in the field better prepared to extricate himself from such a precarious position than Watson.

And Watson knew it.

That’s why when his caddie, the late Bruce Edwards, exhorted Watson to “Get it close,” Watson replied with obstinate determination: “I’m not going to get it close; I’m going to make it.”

He popped the ball into the air, watched it land and begin racing down the slope, and then it careened into the flagstick and dropped in, breaking the deadlock with Nicklaus, who 10 years earlier had bounced his own ball off the flagstick at 17 to set up a kick-in birdie and secure his third U.S. Open title. As the ball disappeared, Watson took off on a mini-victory lap around the edge of the green,then jerked around and, pointing at Edwards, said, “Told you so!”

|

Caddie Bruce Edwards (left) and Tom Watson survey a hole during the 1982 U.S. Open. (USGA Museum) |

A birdie-4 at 18 gave Watson a 2-under-par 70 and 6-under 282 total, surviving the Nicklaus onslaught that included a stretch of five straight birdies in a round of 69 that put him at 284 – six shots better than his winning score from the ’72 edition.

Bill Rogers, who had begun the final round tied for the lead with Watson at 212, wagered that his playing partner could have hit the shot 100 times and “couldn’t get it close to the pin, much less in the hole.”

“A thousand times,” Nicklaus estimated.

At the start of the week, Watson didn’t figure that his odds of winning were even as good as 1,000-to-1.

“I didn’t think I had a chance in a million to do well,” Watson, now 60, recalls. “I was swinging awful. I was hitting it sideways, and I wasn’t even chipping all that well. My putting was about the only thing I could rely on.”

As the first round neared, Watson struck upon an idea: forget about the golf swing. “I already figured that I was going to miss a lot of greens, so I spent almost all my time practicing chips and pitch shots around the greens,” he explained. “The greens are like bowls at Pebble Beach. I hit a lot of shots from the downslopes with lies just like the one I had on Sunday at 17. I practiced that a lot, and I have to credit that to the shot I chipped in. I was confident in my ability and my preparation. I was actually pretty comfortable with what I was facing at the time.”

That says something, given the pressure of the moment and how badly Watson wanted to win the U.S. Open after finishing in the top-10 in six of his first 10 appearances and wearing the mantle of the man to beat in the most recent editions.

Then again, Watson, whose two victories in ’82 prior to the Open had come via sudden-death playoffs at the Los Angeles Open and Sea Pines Heritage, had put himself under pressure all week. Just as he figured, his golf swing was not up to major standards. But his game management was, and that kept him in the championship.

On Thursday, he was three over par through 14 holes, but managed to birdie three of the last four coming in for an even-par 72. On Friday, he was three over after 15 holes, but birdied the final three for another 72.

“That I managed to get back to square each of the first two days was a big key,” said Watson, who won the Bing Crosby Pro-Am at Pebble Beach in 1977 and ’78 and graduated from nearby Stanford University. “I was terrible off the tee. I was so far off line … if you hit zero to 10 yards off, you were dead, but if you were 20 yards offline you were OK, because you were in the gallery where the grass was trampled down. I was in with the gallery.”

But that accidental tourism ceased in the final two rounds. After play on Friday, Watson marched to the practice tee and sorted out his swing fault. “I found that if I kept my arms and my body on the backswing tighter together, I could rotate through on the same plane,” Watson remembers. “Once I did that I started striping it. I turned to Bruce and said to him, ‘I’ve got it.’ You always wanted to hear the three words: ‘I’ve got it.’ That meant I had found something, and I could repeat it. I could make it work.”

|

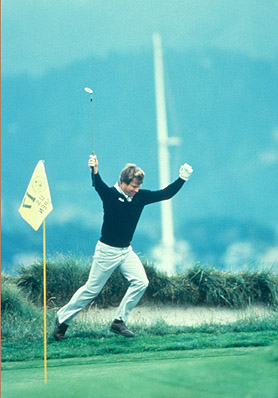

Euphoric moment: Tom Watson begins celebrating his chip-in on the 17th hole. (USGA Museum) |

Fortuitously, the two-day stall didn’t hurt Watson – or anyone else. He was only five behind 36-hole leader Bruce Devlin when Saturday’s third round commenced, and with the winds calming down, Watson and a slew of others attacked a more vulnerable Pebble Beach. Peter Oosterhuis and Lanny Wadkins, who had won the 1977 PGA Championship at Pebble, led a record group of 22 players who broke par with 5-under 67s. Watson’s 68 put him in the final pairing with Rogers.

On Sunday, Watson, who made his U.S. Open debut a decade earlier at Pebble Beach with a respectable tie for 29th as Nicklaus ruled the championship, missed only one fairway and a handful of greens and was going along steadily. But Nicklaus was a few groups ahead making a determined run toward a fifth Open title. When Watson’s 2-iron at the 17th found the rough, the Golden Bear was certain he would at least be in a playoff, as Watson was staring at bogey and would need birdie at the famed home hole to force an 18-hole Monday playoff.

But Jack should have known that 17 was the place where his majors went to die, at least around Watson. It was at the 17th at Augusta National Golf Club in 1977 that Watson sank a crucial birdie to beat Nicklaus by two and win his first green jacket. A year later at the British Open, in their “Duel in the Sun” at Turnberry, when the two men had pulled away from the pack, Watson again seized the upper hand with a birdie at the penultimate hole.

Watson scored a hat trick with his improbable birdie at Pebble Beach.

“That shot at 17 meant more to me than any golf shot I ever made,” Watson said at the time.

All these years later, that sentiment hasn’t changed or faded, since it enabled him to win what he regards as the most precious of his eight major championship victories.

“Honestly, the U.S. Open was the one tournament I wanted to win the most,” says Watson, a five-time British Open champion. “It’s our National Open. I live in this country and I am an American citizen, born here, so it naturally meant just a little bit more to me. It’s the benchmark of my career as far as what I wanted to do in the game.

“I remember talking to Sam Snead many years ago, and he talked about his heartbreaking loss in the 1939 U.S. Open [when he triple-bogeyed the last hole at Philadelphia Country Club], and he told me, “I’ve never gotten that quite out of my head. If I’d have won that one, I might have won 3 or 4 more of them. It just meant that much.”

“I fully understood what Sam was telling me,” Watson added wistfully. “It does mean that much if you’re an American golfer. It does mean that much.”

Dave Shedloski is an award-winning freelance writer whose work has previously appeared on usga.org and USGA championship sites.